http://campominutemen.blogspot.com/2...man-britt.html

http://www.sandiegoreader.com/news/2010/mar/24/cover/

The Wild Wild East

By Chad Deal | Published Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Text size: A | A | A

E-mail the Editor

The Wild Wild East

Brandon Stockwell, a film student at SDSU, climbs to the top of the border fence south of Campo and examines the rolling desert ridges of rural Mexico. The day is bright, the winter air clean and mild. Stockwell considers how the scenery will translate to film. Would black and white or color be more effective? And what about the soundtrack? Stockwell is exploring the prospect of producing a documentary on border policy as a school project.

A motorbike appears in a plume of dust on the American side, and the helmeted driver yells, “What’s your citizenship?” Before Stockwell can answer, a Border Patrol truck that’s following behind skids to a stop, and the half-amused agent says, “Oh, never mind. You’re definitely a gringo.” The men vanish in a haze of dirt, and it occurs to Stockwell that he has just had his first encounter with a Minuteman.

The Campo Minutemen are a small group made up primarily of retired veterans who work in cooperation with the Border Patrol to prevent illegal immigrants and drug runners from entering the United States. With the aid of night-vision binoculars, electronic sensors, and off-road vehicles, the Minutemen act as an extra set of eyes and ears. Most of them carry or at least own firearms. However, the Minutemen exercise a rule of noninterference with border crossers. Their function is to inform the agents of sightings and to let them take care of the rest.

The fence is made from Vietnam-era corrugated-metal landing mat. It is easily overcome by a simple climb and a hop in a matter of seconds. Riddled with gaps and occasionally nonexistent, the fence is as porous as a cobweb, a veritable monument to futility.

The Minutemen camp sits near the fence a few miles down a dirt road off Highway 94. A handwritten sign reminds passersby to “WATCH BORDER” and “STOP illegal immigration.” A generator drones beneath an oak tree. Motion sensors leer from rusted fence posts. Several American flags, tattered and faded, flitter in the arid afternoon breeze. Once teeming with eager patriots answering a call to arms, the camp now appears desolate and run-down. Only four trailers remain, one of which is full of trash.

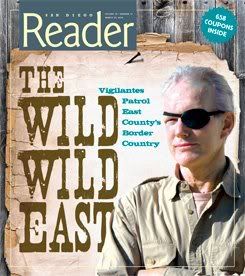

Stockwell gets in his silver sedan and follows the border road east. Rumor has it that a man lives out here somewhere, set away from the rest of the Minutemen in a truck on a hilltop. To the other Minutemen he is “Kingfish,” an archetype, one of the last remnants of the old guard who first arrived in the summer of 2005. The local Border Patrol agents refer to him as “the Pirate” on account of the patch he wears over his left eye. But to Stockwell, the man assumes a mythic personage — he is an Obi-Wan Kenobi of sorts, a backcountry sage who roves the desert highlands alone, weathering cold nights and dubious circumstance.

The road is slick and steep. Stockwell’s car groans as it inches over a dusty hill. Chaparral, granite boulders, and the occasional roadside cactus dominate the expansive scenery. Border Patrol agents watch his progress, occasionally returning his timid wave, often stopping him to ask what brings him out here. They are alternately interrogative and congenial. Small talk is exchanged, but any questions make the agents suspicious and aloof. If Kingfish is Obi-Wan, the Border Patrol agents are Imperial Stormtroopers. They are the ultimate authority in this no-man’s-land.

The new section of wall becomes visible, a towering, rusted monolith of vertical metal slats that extend at least 20 feet skyward and 6 underground. There is no climbing the new wall. Furthermore, the spaced slats allow the wall to be see-through while remaining impassable, a bitter slap to the jowls of potential crossers. But just a few hundred yards to the east, the new wall ends, giving way to a shoddy stretch of landing mat and old rebar.

A few miles out from the main camp, Stockwell spots him. Parked high up on a vantage point beneath a power pylon, the truck occupies the best real estate around. Stockwell pulls over to the side of the road and makes his way through a maze of scrub brush and boulders, contemplating his intentions. What should he say? Will he be welcomed? Should he have brought some beer as a peace offering? Spare batteries as a thoughtful gift?

Stockwell crests the hill, and there he is, Kingfish, smiling and waving as if he’d been expecting Stockwell all along. A black dog bounds through the brush, smelling Stockwell’s hands. “Come on up,” Kingfish says. He stands tall in a plaid long-sleeved shirt and tan slacks, a nine-millimeter pistol tucked in the belt. A sticker in his camper window counsels, “If you can read this, thank a teacher. If you can read this in English, thank a soldier.” Beneath a wool beanie, his good eye scrutinizes the guest with a mixture of warmth and curiosity. “What brings you out here?” Kingfish asks.

“Well,” replies Stockwell, “I suppose I’m here to ask you the same.”

Britt “Kingfish” Craig says he has long felt a deep-rooted sense of appreciation and respect for his country. As a young man, Craig went to Vietnam to defend the American way of life, the national dream forged and handed down to him by his predecessors. Craig was wounded and given a medical discharge, but his sense of duty remained strong. While living in St. Augustine, Florida, in 2002, Craig ran for a seat in the state’s House of Representatives on behalf of the Libertarian Party. He received 11 percent of the vote.

Encouraged by his success, Craig considered running again but found a more immediate means of defending the dream in April 2005 at a Minutemen gathering in Arizona. Over 600 vigilantes showed up for the meeting at the border south of Tombstone. In June, Craig and several others relocated to Campo, where for months they contended with student demonstrators who accused them of being racists and over-the-hill eccentrics. As time went by, the fervor of both protestors and fellow Minutemen fizzled out.

Now Craig is one of only a handful left in Campo. He sees his time on the border as a way of completing his term of service to the American people, cut short years ago by the loss of his eye.

“I believe in all my heart that we have the all-around better society here in the United States,” says Craig. “The idea that somebody born in Mexico City can have the birthright of someone born in Los Angeles or Anniston, Alabama, just isn’t right. It isn’t theirs. It’s ours.”

Craig recalls the day last summer when agent Robert Rosas was killed in the line of duty. Rosas had been parked about 50 yards from Craig’s truck on the evening of July 23, 2009. They had exchanged small talk and joked about Craig’s aggressive Chihuahua.

“Agent Rosas told me they were tracking four people,” Craig relates. “I walked back to my truck and, just out of the force of habit, scanned the border with my optical device. I saw two people standing just inside the wall. One pointed up at me. I instinctively shied away because I knew I was being silhouetted in the sunset. So I ducked down behind the truck and tried to reacquire them visually, but when I ducked, they ducked. I saw them for about a second and a half. I will always regret not sitting there for about five seconds and describing them to myself. That’s how you remember, you know. ‘Blue pants, red coat.’ But I walked up to Rosas’s truck and said, ‘I think I may have seen a couple of your guys down there.’ And Rosas said, ‘That’s okay. The scope truck’s got them.’ As he started away I jokingly asked him, ‘You sure you don’t want to take the attack Chihuahua with you?’ And he said, ‘Sure, throw it in the back of the truck. We’re going to catch these guys. I’ll come back and tell you about it.’ And that’s probably the last thing he said person-to-person to a human being. He drove off over the hill.”

This was at 8:40 p.m. Around 8:53, Craig heard four spaced gunshots followed by four fast shots. He made the call within two minutes.

“I told them, ‘I’m not sure if it’s on the American side or just over the border.’ A truck got down there about five minutes later. And then, you’ve never seen so many vehicles and helicopters out here in your life.… It was quickly discovered that Rosas’s gun was missing.”

The police began a manhunt for the person who had Rosas’s stolen pistol and soon found a suspect. The incident was the first on-duty slaying of a Border Patrol agent in ten years.

“[The police] came up with this fat, dreary guy with a big old beard [Ernesto Parra Valenzuela, 36],” says Craig. “A gangster. He looked like the drunk from The Andy Griffith Show. He’s holding a nine-millimeter Beretta in this supposed police lineup; you know, because everyone goes to a police lineup holding a gun. Most agents carry a Beretta, but Rosas had a different pistol. So they tried [to pin him as a suspect], but that one didn’t fly.

“Then they came up with this kid who the government of Mexico turned over on the condition that he couldn’t face capital punishment. The fact that he was 17 at the time of the killing gave him protection. They tried to say [the perpetrators] were trying to strong-arm rob agent Rosas. Now, [the perpetrators] didn’t have a weapon. Agent Rosas was in uniform, so he wasn’t going to have much money on him anyway. Being a Border Patrol agent, he was guaranteed to be less than 55 years old, in good shape, and armed. The kid claimed he was with some people, but he didn’t know who they were. If you are planning to rob an armed Border Patrol agent, you’re going to know the people with you. I know three or four of the true killers are still out there.”

In November, Christian Daniel Castro Alvarez pleaded guilty to murdering Rosas during an attempted robbery. He is expected to face life in prison.

But the official story that Rosas was engaged in a typical foot pursuit at the time of the shooting doesn’t ring true with Craig. “One of the revealing things about the Rosas killing that doesn’t make sense is that he didn’t close the door of his truck. Whenever an agent gets out to track somebody, they always close and lock the door. He must have responded to something disturbing or critical real fast. He wasn’t tracking anybody in the normal sense of the word.”

Such activity is in accord with much of what Craig has observed in his four and a half years on the border. “I’ve seen people who come to the border, stooge around, and I have photos of very similar-build people [as the ones spotted the day of the shooting] fooling around the border after the incident. I don’t know what they’re doing. Many people are out here doing things that don’t make any economic sense. These people may very well have come over to hijack an agent just to show that they could. It makes no economic sense, but it makes great political sense. It would show that they could terrorize the U.S. police the same way they terrorize the Mexican police. Last week there were five people who crossed over and went directly to agent Rosas’s memorial cross. They never did anything to make any money. They had a different motive. And I believe that motive is something political — minor-league guerilla incursions against the law.”

A few years ago, Craig spotted a group of about 15 people dressed in black with red bandannas. “Probably they weren’t real Zapatistas, but they were wannabe Zapatistas. And they weren’t making any money. They were entering the United States illegally in what amounts to revolutionary rebel uniforms. For practice? I don’t know. For thrills? I don’t know. But I believe there is a political motivation. And I think [the political motive] makes a lot more sense than the idea of trying to strong-arm rob an officer of the law. Maybe they are trying to get some sort of overreaction from the Border Patrol. The worst case of Border Patrol antagonism I’ve seen is when about 40 people from the Mennonite Church over there crossed the border and had a wedding. Sometimes people throw feces at the Border Patrol from across the fence. It’s not going to make you any money. It’s not classic criminal activity. Throwing rocks at an armed man? Robbing an armed man? Dressing like revolutionaries and crossing the border? It makes no sense economically. It’s a real assault on the border — trying to destabilize the border to the point where it doesn’t exist.

“If they only wanted to rob agent Rosas, they didn’t need to shoot him once in the neck and three times in the back of the head. It was an execution. The whole thing looked like a setup in order to kill somebody. The fact that five people came across about ten days ago, went directly to the monument, and got chased off tells me something more is going on. It’s provocation. It’s been going on in one way or another ever since I got out here.” This type of activity accounts for about half of the movement Craig observes on the border.

Craig bears no ill will toward the men and women who enter the country illegally. He acknowledges that he would do the same were he in their situation.

“Anybody is going to try to better themselves. Anybody is going to try to feed their family. But that doesn’t make it right.”

Because illegal immigrants are often willing to work for a fraction of what U.S. citizens will work for, Craig contends, entire industries are hurt, putting Americans out of work. Furthermore, illegal immigrants are subject to mistreatment ranging from being overworked and underpaid to not being paid at all.

“What’s he going to do?” asks Craig. “Call the cops? Just as bad as you want to be is how you can treat him. And that has screwed up the deal for everybody in the country.”

With a furrowed brow, he takes a long look at the expanse of land south of the fence. To the untrained eye, both sides appear identical — sparsely populated, serene, picturesque. But Craig’s singular vision perceives that subtle branding that separates north from south. Craig’s American dream ends at that wall. It butts up against it and goes no further. The dream that some semblance of decency and goodwill should circulate among the common psyche, the dream that young men and women should be allowed to grow up in a safe society ruled by temperance and reason, the dream that hard work is rewarded with fair pay and everyone who exerts an effort gets what he needs to pursue his happiness — this dream belongs to us, Craig knows, provided we are willing to claim it as our own.